Circumcision has been passed down like a family heirloom—handed off without question, wrapped in vague promises of hygiene, tradition, and medical “benefits.” It slips under the radar, barely scrutinized, yet leaves a permanent mark in its wake.

Cutting off a piece of the body without consent isn’t routine—it’s radical. And the foreskin? It’s not a glitch in the male anatomy. It’s functional, sensitive, and designed to stay put. The idea that it’s disposable has more to do with outdated rituals than sound medical reasoning.

We live in a time when bodily autonomy is championed, yet this one area gets a pass. No one questions it—until it’s too late. Parents make the call before the child has a voice, and that decision echoes for a lifetime.

It’s time to challenge the narrative that cutting away healthy tissue is somehow an upgrade.

In this article, we’ll strip away the layers of tradition and medical half-truths to reveal what’s really at stake. If we’re going to talk about circumcision, let’s be honest about what’s being sacrificed.

The Foreskin: Anatomy with a Purpose

Most conversations about circumcision gloss over the foreskin, reducing it to “extra skin” or a hygiene liability. But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

The foreskin is an integral part of the male anatomy, designed by millions of years of evolution. If the foreskin were as useless as circumcision advocates claim, why does it persist across almost all mammals?

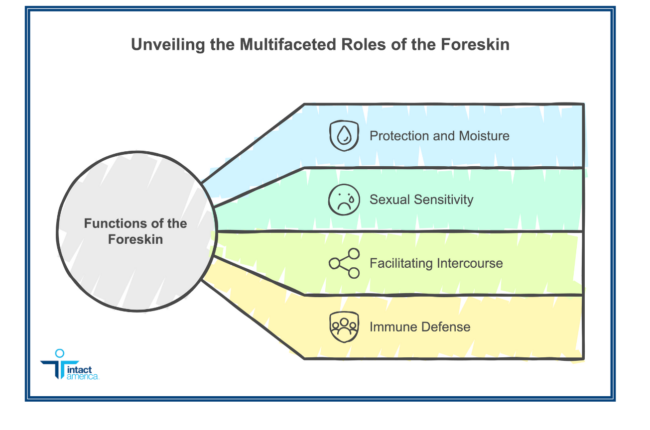

The Overlooked Functions of the Foreskin

1. Protection and Moisture

From infancy through adulthood, the foreskin serves as a protective barrier for the glans (head of the penis). It keeps the glans moist and prevents friction from clothing. In infants, this protection can prevent irritation, infection, and even diaper rash. As men age, the foreskin continues to shield the glans from abrasion, keeping the area sensitive and smooth.

2. Sexual Sensitivity

One of the most significant functions of the foreskin is enhancing sexual pleasure. With over 20,000 nerve endings, the foreskin is one of the most sensitive parts of the male body. It plays a crucial role in sensation and pleasure during intercourse, acting much like the clitoral hood does for women.

3. Facilitating Intercourse

The foreskin’s natural gliding action reduces friction during sex, making intercourse more comfortable for both partners. Without this mechanism, circumcised men often require additional lubrication, and their partners may experience increased dryness or discomfort.

4. Immune Defense

The foreskin contains Langerhans cells—immune cells that help defend against pathogens. Removing this barrier leaves the glans more vulnerable to infections, contradicting the belief that circumcision inherently promotes better health.

Why Is This Overlooked?

Despite clear evidence of the foreskin’s importance, it’s dismissed as expendable. This oversight reflects not science, but deep-rooted cultural biases and a reluctance to question long-standing traditions.

The Origins of Circumcision: A Ritual Turned Medical Procedure

Circumcision has been around for thousands of years, but its origins are rooted in ritual, not medicine.

Religious and Cultural Beginnings

In religious contexts, circumcision is a rite of passage. In Judaism, it symbolizes a covenant with God. In Islam, it represents purity and adherence to tradition. For many indigenous cultures, circumcision marks the transition into manhood.

But these rituals were never based on medical necessity.

The Victorian Obsession with Sexual Control

In the Western world, circumcision gained traction in the 19th century as an anti-masturbation measure. Victorian-era doctors believed masturbation caused mental illness, tuberculosis, and epilepsy. Circumcision was seen as a way to diminish sexual pleasure, discouraging boys from touching themselves.

It’s unsettling that a practice rooted in sex-negative pseudoscience continues to thrive in modern medicine.

Medical Myths: The Flawed Justifications for Circumcision

Circumcision’s persistence in modern medicine is propped up by a series of half-truths and exaggerated benefits.

Myth 1: Circumcision Prevents UTIs

Yes, circumcision slightly reduces the risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in infants. But the statistics tell a different story:

- UTIs in boys occur in only 1% of cases.

- Antibiotics treat UTIs effectively without the need for surgery.

Performing surgery to prevent a rare, easily treatable condition makes no logical sense.

Myth 2: Circumcision Reduces HIV and STIs

Studies have shown circumcision reduces HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. However, these studies are often cited out of context.

- Condoms and sexual health education remain far more effective in preventing STIs.

- Western countries with low HIV rates derive minimal benefit from circumcision.

Circumcision as a tool for STI prevention is a blunt instrument in a world with better options.

Myth 3: Circumcision Prevents Penile Cancer

Penile cancer is exceedingly rare:

- Less than 1 in 100,000 men develop it.

- Factors like smoking and HPV are more influential than the presence of foreskin.

Suggesting circumcision as a cancer prevention tool is fear-based, not evidence-based.

The Ethical Minefield: Consent and Bodily Autonomy

Circumcision raises profound ethical questions that often get swept under the rug by tradition, cultural norms, or parental preferences. But at its core, circumcision represents a violation of bodily autonomy. This is a deeply personal, human rights issue that touches on consent, bodily integrity, and the right of every individual to make decisions about their own body.

The Consent Dilemma

Infants cannot consent. They can’t express preferences, weigh risks, or voice objections. Yet, circumcision permanently alters their bodies in a way that can never be undone. This decision is made not by the individual who will live with the consequences, but by their parents, often under the influence of outdated medical advice or cultural pressures.

Circumcision has been performed for so long, and on such a large scale, that people rarely stop to question it. But normalcy doesn’t equal morality.

Bodily Autonomy is Non-Negotiable

Bodily autonomy—the right to control what happens to your own body—is one of the fundamental principles of medical ethics. The concept of “First, do no harm” lies at the heart of responsible medical practice. Circumcision contradicts this principle by performing permanent, non-consensual surgery on infants who cannot advocate for themselves.

Consider this:

- We fiercely defend bodily autonomy for adults. Medical professionals need consent for even minor procedures.

- Children’s bodily autonomy is protected in other contexts. Parents can’t authorize cosmetic surgery for purely aesthetic reasons.

But for some reason, circumcision escapes this scrutiny.

The Weak Justifications for Circumcision

Many parents justify circumcision based on emotional reasons:

- “I want him to look like his dad.”

- “Everyone else does it.”

- “It’s just tradition.”

None of these arguments address the child’s rights or best interests. Cosmetic or emotional motivations should never override bodily integrity. Parents can guide their children’s choices—but permanently altering their bodies without medical necessity crosses a line.

The ethical dilemma becomes even clearer when you acknowledge that many men grow up to regret the procedure. This permanent decision should belong to the individual—not the parent, not the doctor, and certainly not societal norms.

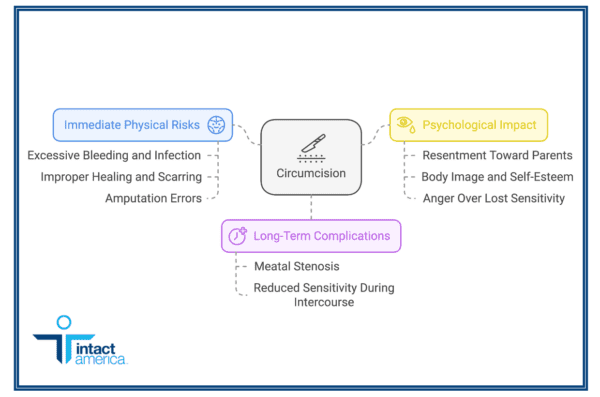

The Hidden Harms of Circumcision

Circumcision is frequently marketed as quick, safe, and routine. The reality is far more complicated. Like any surgery, circumcision carries risks—some immediate, others that surface years later. These risks are often minimized or ignored by those who perform and promote the procedure.

a. Immediate Physical Risks

Circumcision may seem straightforward, but cutting away living tissue from a newborn’s most sensitive area is anything but.

1. Excessive Bleeding and Infection

Newborns have delicate immune systems. Any open wound, including circumcision, creates an entry point for infection. Excessive bleeding can also occur if the surgical site is not properly monitored or if the child experiences complications in clotting.

While rare, some infections lead to sepsis—a potentially life-threatening condition.

2. Improper Healing and Scarring

Not all circumcisions heal properly. In some cases, the wound may heal unevenly, resulting in disfigurement or scarring. Poor healing can lead to tight, painful adhesions or the partial fusion of the glans to the remaining foreskin.

3. Amputation Errors

Yes, this happens. Sometimes too much or too little skin is removed, leading to either excessive tightness or residual foreskin. Severe cases can cause disfigurement, pain, or sexual dysfunction later in life.

b. Long-Term Complications

While the immediate risks often fade, the long-term consequences of circumcision can persist throughout adulthood.

1. Meatal Stenosis (Urethral Narrowing)

A common complication of circumcision is meatal stenosis, a condition in which the opening of the urethra narrows, causing pain and difficulty urinating. This condition rarely affects intact boys.

The friction from diapers combined with a lack of foreskin contributes to inflammation and narrowing of the urethral opening.

2. Reduced Sensitivity During Intercourse

One of the most controversial long-term effects is the loss of sexual sensitivity. The foreskin contains thousands of nerve endings that are severed during circumcision. Men circumcised as adults frequently report that their sexual experience diminished significantly.

If adults feel this loss, imagine the magnitude for infants, who never have the chance to know what was taken from them.

c. Psychological Impact: Circumcision Regret

The psychological aftermath of circumcision often surfaces much later in life. As awareness around the function and importance of the foreskin grows, many men are left feeling angry, betrayed, or violated. This emotional response is now referred to as circumcision regret.

1. Resentment Toward Parents

Some circumcised men feel anger or disappointment toward their parents, believing the procedure was unnecessary and unjustified. This can strain family relationships and lead to unresolved resentment.

2. Body Image and Self-Esteem

Circumcision can impact body image. Some men report feeling incomplete, mutilated, or different from their peers. The idea that a piece of their anatomy was removed without consent can cause deep emotional wounds.

3. Anger Over Lost Sensitivity

The more men learn about the foreskin’s function, the more they question what was taken from them. Many report a sense of loss, betrayal, or regret that they were deprived of the full range of sexual sensation.

Conclusion: Questioning the Unquestioned

Reevaluating this long-standing practice empowers future generations of men to have authority over their own bodies. True bodily autonomy begins with the ability to make informed choices, and that choice should belong to the individual.

Cliff Joseph

March 19, 2025 9:16 pmI am not circumcised and are glad my parents chose not to cut me. In school some boys would ask what was wrong with my penis, I tole them all boys are born that way. Some thought they were born without foreskin. I was taken back at their ignorance of their own body. I was taught by my father how to take care of my private area since I was young. I have never had a problem and my wife loves my penis the way it is. The boys/men who are circumcised will never have the right to make the decision to be circumcised or not!